The Four Lives of Andrzej Maria N. Borkowski

A Metaphysical Shaggy Dog Story

A small glass painting, a gift from my wife, hangs close to where I write. It depicts an angel or, rather, an angel of sorts, its character more secular than divine, whose face could be F. Scott Fitzgerald's, especially with the hair parted so close to the middle, although the red daubs on the cheeks suggest a more clownish demeanour, a touch of Fellini maybe.

This man-angel, whose wings look like the insides of the two halves of a scallop shell, wears pink woolly pantaloons, clutches a magician's wand, and stands on a circular base of blue upon which is inscribed, in white, in a receding triangle, the letters ABRACADABRA. There's a complex, though not wholly proven, etymology here. Among the various interpretations ascribed to this ancient magical formula are the words 'I create as I speak' from the Aramaic avra kedabra which has been taken to be a reference to God creating the universe. It's not a bad motto to have nearby as one struggles to make flesh of one's own scribbles, or, as in this case, another person's garbles.

I do not mean to be rude. The Wimbledon Pole who painted this image, Andrzej Maria Borkowski, speaks at such speed that when transcribing him from my little blue recorder onto the page, it's all I can do to follow the wild leaps from phrase to phrase. The spaces in between are filled with despairing cries, verbal erasures ― 'No, no, no, no!' or 'It's boring, boring!' (this usually at a point when I want him to continue) ― and other sounds of a mostly zoological nature. I've never known a man who can take up so much sonic space. There's got to be a metaphysic here. I remove my earphones. The figure on the wall suggests an analogy, although not a wholly satisfactory one; and it is this: glass painting needs to be done in reverse, so when composing a face, for example, one begins by painting the pupils of the eyes. It is, in short, a medium that does not allow for any correction of mistakes. And so it is with Borkowski that spoken language is pulled inside out, its entrails the first thing to emerge. There's no going back to any original grain of sense because sense has yet to arrive. There is only a forward charge ― the Polish Cavalry is him alone. Maybe the solution is to translate him into Polish, which, sadly, is not a language I speak, and then back into English again. Joking aside, working his story into something approaching the comprehensible did at times involve my putting him at a double remove.

What is revealed, once spread flat on the table, is a singular intellect whose mode, if one were to translate this into visual terms, is cubist rather than representational. Of his divers art, he says it owes more to simultaneity than to sequentiality, and likewise when he speaks all comes at once. There is no want of intelligence ― it simply operates on a different plane. The words, though, they seem so very slow on the page. A kind of alchemical process seems to have taken place, a rendering of base materials into pure, and yet I have to ask myself whether this heavily edited, much reduced, portrait is at all true. The very fact I have ironed out the crinkles seems to play Borkowski false. You'd really need to tear out these pages, crumple them, shove them in your pocket, and then, maybe a day or two later, try to flatten them out a little, to get some sense of what he's really like.

Soutine might have painted his face, Wyspianski his Pilsudski moustache.

The following is an autobiographical note:

There are four people in me, hence the four names ― Andrzej, Michal, Maria and 'N', all born in Warsaw out of the Teutonic Knights' and Tartars' blood of his Polish ancestors. Andrzej is an art historian and critic, graduated at Warsaw University (M.A.) and London (M.A. Courtauld Institute). He is a sceptical and sarcastic man, but his art can be fun. He teaches at Brighton University in the School of Art. Michal is an angel and he hardly ever touches the ground. He flies. His is a mercurial nature. It is probably he who is the actor. He worked in theatre and dance and even did some films with Melanie Griffith and one with Sting. Maria is his third name. She is a woman, the Earth, and probably a better artist and poet than Andrzej, and through her I feel. 'N' is my fourth name. It might be an animal, wolf or ape. It is in me and plays with the other three.

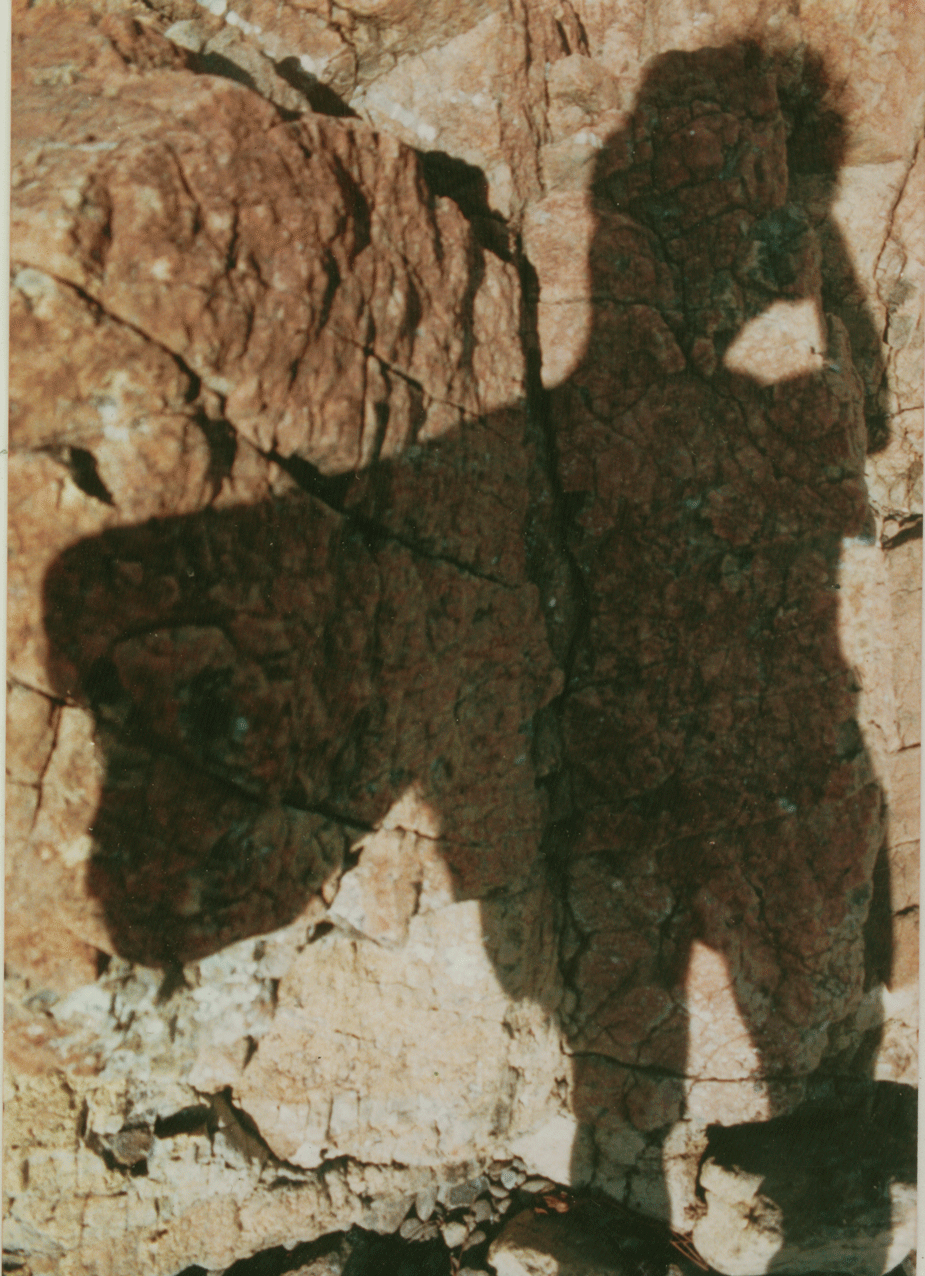

And so, following on his own slightly madcap scheme, Andrzej Michal Maria N. Borkowski shall be here presented as the possessor of four lives. Admittedly the divisions between them are a bit arbitrary at times, and besides, I do not wish to put him, or, rather, all four of him, inside a verbal straightjacket. Anyway he moves faster than language. Also he has illustrated those lives of his with photographic shadow images, which he took mostly in Cappadocia, stark naked, away from the eyes of the populace. With a hand-held camera he took pictures of his own shadow cast against rock and sand and trees. The trick is to keep the shadow of the camera out of the picture. The best time to photograph, he says, is between three and five in the afternoon when the sun is not too harsh because too much contrast spoils the effect. Those strange, hauntingimages reflect the multiplicity of one's existence. The incredible thing is that he should have thought of doing them in the first place.

'You project your inner story outside,' he says.

The ancient Greeks regarded shadow as a metaphor for Psyche, and that great myth-catcher Sir James Frazer writes of the primitive: 'Often he regards his shadow or reflection as his soul, or at all events as a vital part of himself, and as such it is necessarily a source of danger to him.' Jung, looking deeply into his shadow, maybe deeper than he intended to, saw in it the instinctive and the irrational ― 'the thing a person has no wish to be'. 'As the Sun is the light of the spirit,' writes J.E. Circot in his Dictionary of Symbols, 'so shadow is the negative "double" of the body, or the image of its evil and base side.' The general take on Shadow is that it's too dark a country to make one's abode. For Borkowski, on the other hand, smiling explorer of the mind's unlit places, it represents wondrous possibilities. Instantaneously, or, rather, simultaneously, as he flung phrases here and there, he drew on aboriginal art, the cave paintings at Lascaux, Plato's Cave, a Hopi legend concerning copulation with the earth, the physiognomist Johann Kaspar Lavater's silhouette-making machine, Adelbert von Chamisso's Peter Schlemihl, Athanasius Kircher's writings on the Lanterna magica, Cubism, The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, animism, the early photographs of Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz, and finally his own childhood memories.

Andrzej

What's that growing out of the middle of his head? What life is this that clings to such a barren substance? Could it be analogous with all we attempt to do, when we wrest something from nothingness? Borkowski has as many professions as he has names ― art historian, teacher, painter and actor. (I am tempted to add 'contortionist' because Guinness paid him £2,500, and a trip to Portugal, to do an advert posing as a sadhu after the original sadhu, that is to say, a genuine one, had failed to contort sufficiently.) Appropriately enough, given that he has many other guises as well, what first brought him to this country was the stage.

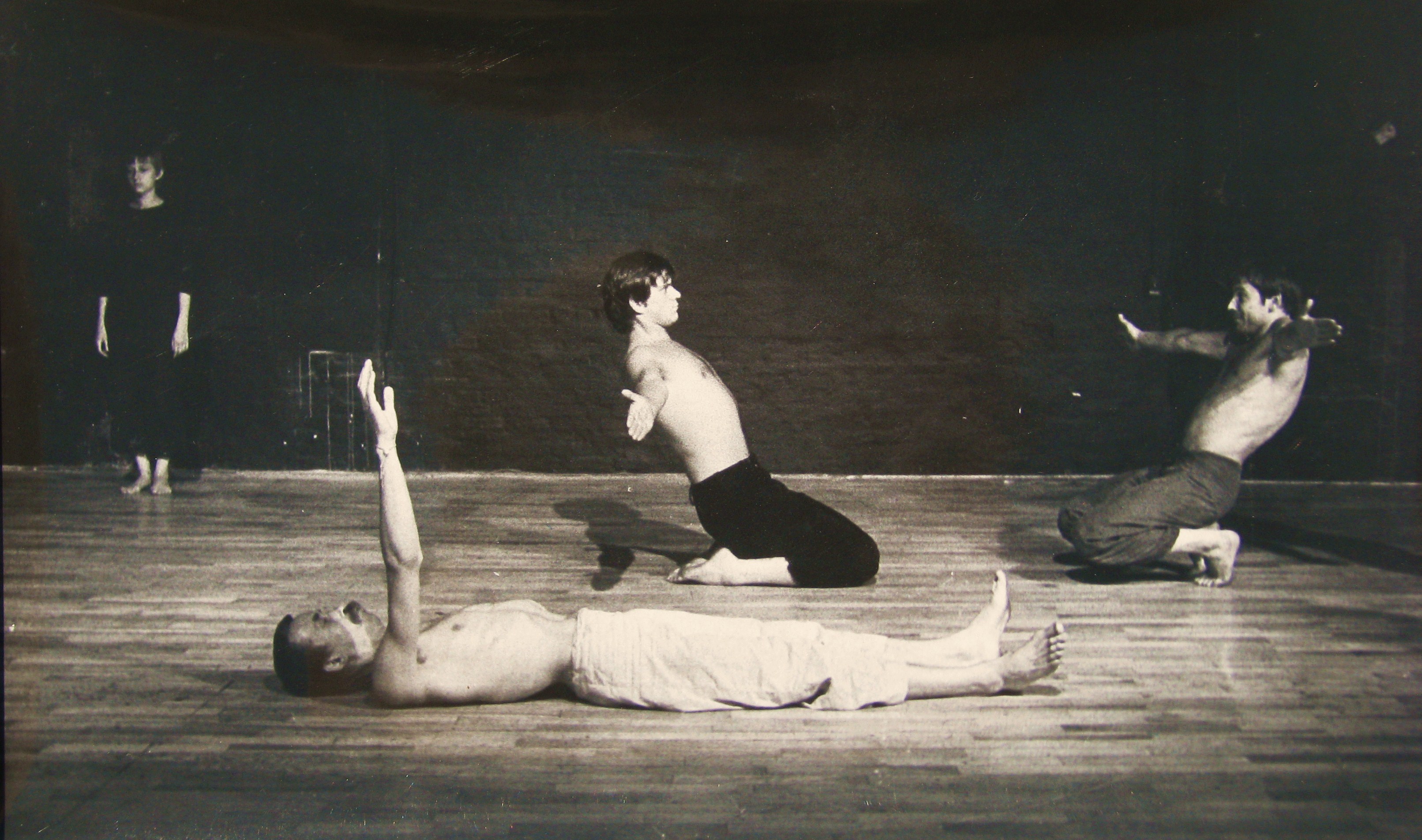

'I'm not sure to what degree I can be called an émigré because I was asked to join a theatre company here. So it wasn't the usual business of making one's way through a building site towards some idea of selfhood. In 1967, I applied to the Fine Arts Academy in Warsaw. There were only a limited number of places available, but although I was accepted on the basis of my work there wasn't a place for me in Warsaw. I'd have to go to Gdansk, they'd said. My mum suggested I apply for art history instead, so I applied to Warsaw University, thinking I wouldn't get in, and was accepted. So I became a bloody art historian, which I never wanted to be. That September, when I started my course, I checked out the student theatres to see if I could do set designs or costumes. I found one looking for set designers, so I joined the queue. There was a nice girl in a neighbouring queue, applying for mime theatre. One thing I knew is that I could never be an actor. My uncle said that because I mumble and speak too quickly, nobody understands me. Another thing I knew is that I liked girls. So I asked her, "What's mime?" She said it was theatre without words. "No words! Really? That's okay!" So I moved into her queue and that same evening I joined a mime troupe. That's how I became involved with theatre. It was not so much mime in the Marcel Marceau sense ― it was more geometrical, more stylistic, and moving slowly towards performance art. I joined one group and then another and then finally, in 1971, a friend of mine, Wojciech ("Wojtek") Krukowski, now director of Centre of Contemporary Art in Warsaw, formed a new group, Akademia Ruchu (The Academy of Movement) and asked me to join. This became one of the most important avant garde groups at that time.

'We didn't use words except as written banners, these sometimes being lines of poetry, so the emphasis was more on fine arts than on literature. This was good for international contact because there wasn't any problem with language. Polish theatre was quite important in those days, mainly because of Jerzy Grotowski, and then there was Tadeusz Kantor with his Theatre of Death in Kraków, which was closer to some of our ideas. With Grotowski, on the other hand, there was a major difference in our attitudes towards theatre in that his approach was deeply psychological in nature whereas ours owed more to a formal neo-constructivist tradition, concentrating on body and image.'

A few years later, a young British director, Stephen Rumbelow, head of Triple Action Theatre, went to Poland seeking inspiration and actors. Poland was still very much a destination for the romantically inclined, especially with its added frisson of political menace, but, this said, or maybe even because of it, it also boasted some highly original theatre. The productions were often so concise that watching them reminded one of the workings of an immaculately constructed watch whose every movement is in perfect harmony with the whole. Student theatre was a particularly potent force and not to be confused with amateur theatre. Clearly Rumbelow did not go there in a haze. This was where major talent was to be found. At his invitation, Borkowski joined his company.

'I came here in that dry summer of 1976. Here I was in London for the first time and I never got to see it! I arrived by train at four in the afternoon. They were waiting for me, and then we crossed the street from Victoria Station to a pizzeria where a Polish waitress served me. What, already! I was desperate to see Big Ben, but instead this van zoomed through London to Newark which is one church, one library, one river and a castle. This was our base. It was spoken theatre, which was different from what I was doing in Poland, but really I came to England for the experience. Why not? The theatre was for me overly dramatic, a bit pretentious and overdone. We did The Idiot and I was Rogozhin. It was all rather alien to me because I had always felt like an independent artist. I had been the main member of Akademia Ruchu and, together with Wojtek, the creator of those performances, whereas here I was just an actor, which I never wanted to be. At Easter 1977, we decided to part company and I stayed on in England until the end of summer. Just before coming to England I had met my future wife, Gabriela. I felt badly about leaving her because I had only met her a few months earlier. She came to England and we tried to survive, God knows how. I taught some workshops and also did illustrations for the alternative magazine International Times but that, too, was difficult because they offered me hashish rather than money. What could I do with hash when I needed to pay my rent?'

Borkowski went back to Warsaw where he rejoined Akademia Ruchu. He also found a job giving lectures at the Fine Arts Academy in Gdansk, the very school he was supposed to have gone to years before.

'Quite by chance, Gabriela, who I knew when she was still in school, was now a first year student in my class. People said I was picking up students. No, I had picked up a schoolgirl! I lived in Gdansk, three days with her, and then four days in Warsaw where I carried on with the theatre.'

'You must have been there when Solidarity started.'

'People always talk of Gdansk but actually the strike began in Lublin. We had come back from a street theatre festival in Rimini, my wife something like six months pregnant, although still performing. Already there were rumours about strikes, and by the beginning of August Gdansk had become a centre of growing tension. I went immediately to the gallery where I gave lectures. As soon as I arrived people began to shout at me, 'Oh, Andrzej, we are going to strike!' The centre of the movement was in the shipyards and various groups, including ours, were joining it. 'Are you with us?' they said. Half the people at the gallery were for the strike and the other half against. I was for it. We got into the car and went to the shipyard. This was a part of our history that could have been mine, but with Gabriela now seven months pregnant and my identification card a Warsaw one, I told them I'd rather stay with her. We returned to Warsaw. So that was the tense first year of Solidarity. An agreement was signed at the end of August 1980 and then the question dragged on and on, as to which would be more powerful, the Communist Party or us. In March 1981, there were Warsaw Pact military manoeuvres, with our communist friends from different countries joining in. There were East German troops in Gdansk and Szczecin. A few months later, we had martial law.'

Grotowski's assistant, Eugenio Barba, who had created his own theatre in Denmark, offered Akademia Ruchu a month's residence in Odense. It was there that Borkowski met Grotowski, one of the century's greatest exponents of avant garde theatre, although by that point he had already begun to move beyond staged theatre, into something which he coined 'paratheatre', which dispensed completely, or at least theoretically, with the idea of an audience.

'I met him a few times. I was invited to work with Stanislaw Scierski, one of Grotowski's main actors. All this anthropological theatre was definitely fascinating, but I was suspicious of all the mysticism and charisma attached to it, that particular brand of seduction. Scierski's workshops would begin at four in the morning, and you'd have to come and wash the floor first. It may have been fascinating to observe, and there really was something pushing me in that direction, but I didn't like those group situations in which one lost all control of oneself. I found that building of a myth, which began with washing the bloody floor, rather scary, and although it might lead to shamanistic experiences, there was a fascistic element in it that I didn't like. It could be a way of getting into your soul, but it wasn't for me.

'At that point Grotowski was doing these swieta or "holy feasts" and was inviting people to a forest in the Polish mountains to work with him for a month, again beginning with physical work, all that hippie stuff. I felt a bit guilty that I hadn't seen more of his work. Obviously he was a legend, but I couldn't really talk to him about theatre. I was afraid he would be deep into theory and all about reaching holiness and also, because I was suspicious of that charisma, I wanted to fight his influence as much as possible.

'I was therefore pleased to discover he was keenly interested in what was happening in Poland. This made him seem like a normal man, caught up in that great moment of Solidarity, at a time when there was a real danger the Warsaw Pact would intervene. Rather than talk about theatre, Grotowski told me about the days he spent on trains in Poland, just talking to people, getting their thoughts on the situation. Also, because I had a short- wave radio, we listened together to the news from there. We discovered that, like it or not, we were both Poles, and that as Poles we had a duty to, and responsibility for, our country. This was discomforting for both of us because it blocked out any sense of normality, but at the same time it was a part of us that we couldn't allow ourselves to forget.

'This may sound deeply pretentious, or maybe even the building of another mythology, but because we were so deeply rooted in our history, we had the sense of having responsibility for our peasants! I met him again, when he came to the Cardiff Laboratory Theatre and there I tried to put questions to him that had more to do with theatre and ethics. I have always been troubled by this problem of "Why should I ask anyone to be interested in my vision?" This is a question any artist must ask of himself.

'Meanwhile I had left Gabriela in Warsaw with a small child, in that hot situation. When still in Odense, I got a telephone call from Richard Gough of the Cardiff Laboratory Theatre with whom I had already worked once, asking me if I'd be interested in joining his company for a festival in Leicester in the summer of 1981. This produced a major conflict in me, between carrying on with an old performance at another theatre festival, and doing something completely new. Although working with Akademia Ruchu greatly satisfied me, I had been very much part of a collective and now I wanted more independence. I really respected Wojtek and he respected me, but there were some elements on which we were in disagreement. I felt a bit trapped, impatient to try something new, and so, for better or worse, after nine years with Akademia Ruchu, I left. There were still a lot of practical problems such as my not having my own individual passport. I returned with the group to Poland, thinking I would go to England from there. Politically it was still a hot situation. I couldn't return my 'group' passport because there wouldn't be enough time to apply for a private one, and, in any case, there wasn't any guarantee I'd get it.

'So I decided to do something a bit illegal and just not bother to return it. This was a bit unfair on Wojtek who was responsible for the group and all the officialdom involved, which, of course, included his having to return our passports. Anyway, I held onto mine and then I negotiated with the authorities that I be allowed to take my wife and daughter. Two months later, I went to Cardiff and then to Leicester, and performed there with the street theatre. I didn't know what to do next. I still had my contract with the university in Gdansk. After Cardiff we went to London and I reconnected with the people from IT. They were doing the final edition of the Alternative London Guide. I did illustrations for it, often slipping into them allusions of my love for Gabriela. I also did a workshop with Alex Mavrocordatos, who I knew from the days of Triple Action Theatre, and who was now with a company called Hesitate and Demonstrate run by Geraldine Pilgrim. They weren't very strong on movement so Alex asked me to do workshops with them.

'That was it. Summer was coming to an end. I couldn't keep a family on this, so it was time to go back to Poland. I had collected so many books, a whole trunkload, and because I knew Hesitate and Demonstrate would be performing in Wroclaw a few days' time, at the beginning of October, I asked them to put my trunk of books into their props. I flew with Gabriela back to Poland, on my birthday, which, as you'll see, was a nice coincidence, returned my passport which was dodgy because it was the wrong one. Wojtek was still furious. The following day, I got a train to Gdansk in order to sign another year's contract for lectures, and because there wasn't enough time to return to Warsaw I caught a train from there to Wroclaw where I met up with Geraldine and Alex.

'Sweet Gerry, this English lady from London, she really was a fantastic artist, very much into B-movies, her performances strongly based on visuals, but quite different from ours in Akademia Ruchu. She relied on props that were authentic objects, their purpose being to convey a sense of magic and nostalgia. She would go to scrap yards to get doors from old trains in order to make a collage of images. Her most successful show was Goodnight Ladies! She was in love with old tunes, men in Borsalino hats, and was very much into spy stories. A couple of weeks earlier, we had been talking about possible future cooperation. So here she was in Wroclaw. I had just returned my passport, signed the contract in Gdansk, and now she says to me, "I have thought a bit more about this and I'd really like you to join Hesitate and Demonstrate." Oh, my God! I said, "Gerry, only two days ago, I was with my wife, looking for a job, and there's no telling what might happen here. I'll do it, yes, but it will be at least half a year before I can begin to apply for my private passport and find a replacement for my lectures. I can't go just like that. Two days ago, I could have. After all, this is not a liberal democracy." A few months later, in January, 1982, I was supposed to have been in New York in Goodnight Ladies! but because of the introduction of martial law a month earlier I couldn't even phone my mother across the street.

'I was stuck. I couldn't call Gdansk, especially Gdansk, because there was no telephone communication. I decided that was it, I wouldn't be able to leave. Now, bearing in mind Gerry's passion for spy stories, here I was, badly needing to communicate with her. I had all these fantasies, and, after all, we knew the Russians could invade any minute. I remember going to my friend who was a pilot with Polish Airlines, and, somewhere in his notebook, writing a letter to Gerry, which later he would tear out, maybe in Athens, maybe in Stockholm, put into an envelope and send to her. I began to think it was hopeless, and that I'd never be able to join her company, but then I heard a Polish punk rock group was touring abroad. I thought well, maybe things are not so tight after all. I went to the Polish Artists' Agency. I had an official contract with Gerry so the only thing left for me was to get a passport. As I could no longer do it privately, I needed a sponsor to cover for me. I asked them for a passport for my wife as well. That took a long time, almost a year. In September, they finally organised a passport for me, but then the Gdansk police told Gabriela they'd lost her passport so at the last moment she couldn't travel. Hoping she would be able to join me soon, I took a boat to England. I didn't think I'd be leaving forever.'

This was to be a major turning point in Borkowski's life, although he did not quite realise it at the time. As any cineaste knows, there's something deeply poetic in the way trains, boats and planes mark those divisions that exist not just in time but in the soul as well.

Michal

Are those not an angel's wings, such as one finds in mediaeval images of warrior saints? Are they not beginning to sag a little? And that hand pressed against the tilted head, does it not suggest disquietude? A worried saint for worrying times? The trousered angel whom a trouserless Borkowski evokes is the archangel Saint Michael or, in Polish, Michal, Commander-in-chief of the angels loyal to God, and he is also patron of police officers, mariners, paratroopers and grocers. If a serpent crawls upon that rock, he'll place his bare foot on it. This is inadvisable. Where's his unsheathed sword, though, and his scales of justice? Are they hidden inside his shadow? Where is justice, within or without? And where's the sword that aims true?

Borkowski continued.

'The story I'm about to tell you, which took place exactly one year later, is quite a different one. It has to do with the number "33". I haven't read much Jung, but when I was in Odense I just happened to pick up one of his books, I can't remember which one, where he presents his ideas regarding the stages of human life and the process of individuation that is supposed to occur in the human personality round about one's 33rd year, which is the age Jesus Christ was when he died. Symbolically, according to Jung, "33" represents the end of life, the point at which one is given the opportunity to die spiritually in order to be reborn in some higher embodiment. All I am saying is that I read this and I panicked, as I still do, about the passing of time. I started making all these calculations, counting the days from the day of my birth onwards, and what I did was to create this inner myth that on my 33rd birthday I would die. I didn't know what kind of death it would be, maybe symbolic, maybe real, but something would happen. I prepared myself for this, not consciously, but it was something I kept returning to, thinking I'd only so many days to go.

'I had been settled in England for about a year. In September 1983, I was in Rotterdam, at De Lantaren Venster Theatre, working on a new production called Shangri La. My birthday would be spent there. Our set was extremely complicated, and we were terribly under pressure, working long days, sometimes twenty hours at a time. Some of us were doing coke, not so much for the effects but simply because of exhaustion. I never wanted to because I was already high enough without it. I was staying at a cheap hotel, the Central, with Alex Mavrocordatos, my old friend from Triple Action Theatre, and after a long day's work we returned there, absolutely exhausted. Alex had some really good grass, which we smoked, sharing music on a walkman. I was just falling asleep when I had this vision. It was God's voice, coming to me in a most beautiful way. It's not something one can properly convey in words. It wasn't a person but a voice, or, rather, a presence. It said: "Well, that's it. This is your 33rd year. You didn't notice because you've been working so hard, but today's the day you'll die. You've had a problem with asthma, you are exhausted, and on top of it all you've had that stupid grass which is too strong. I'm sorry, but that'll be it." It was so frightening. I was sweating. During those last moments of your life you think about those whom you'll be most sorry to leave. I thought about Gabriela and my daughter, Alicia. I took out my photos of them and set them on the pillow so they'd know they were in my thoughts before I died. It was my own little theatre, all this getting ready to die. And then it came, a dark wave, getting darker, darker, and just when I thought that's it, I'm going to die, suddenly there came this flash of enthusiasm, and, soon after, relief that I'd passed through it somehow. The music that had been so low and dark suddenly became ecstatic. It was just the joy of being alive.

'I understood now that my love for Gabriela and Alicia, and theirs for me, had rescued me. And I thought it wasn't meant to be a real death but that symbolic one about which Jung wrote. I prepared to go to sleep when once again this music started, this time even lower and darker than before, and the ironic voice of God returned, saying, although not in words exactly: "What are you talking about, the love of your wife and child? That's ridiculous. They won't miss you at all. Alicia, who is only a year old, won't remember you. She'll probably have another father. So you can't rely on her. It may be a nice idea, but what are you thinking? And Gabriela? Who are you kidding?"

'What He said was true. We'd had a serious problem because when I left for England she was having an affair with a fellow student, which got more and more serious and would eventually be the cause of our separation. And now God was saying to me: "All you did may be very nice and sentimental, but who cares? She will be free of her problem and, by the way, did you really think you'd die because you smoked a few cigarettes? Do you really think you have control over this? No way! This is nothing to do with you. There are bigger things than you. You'll die, yes, but not just because of a few puffs on a joint. You see, Rotterdam is a major port and, as it happens, there is an Arabic terrorist in the room upstairs with a bomb, which right now he is manipulating and which will accidentally explode. You will die not because of your little adventures, but rather because it's time to." All this sounded terribly logical to me. God was telling me to be humble, telling me what a small world mine was, and what a measly thing my idea of death. I was just a link in a network of things that cannot be influenced and which, in any case, I couldn't understand. And maybe because there was such a beautiful structure to this vision, I began to think again, along the same lines. "Who'll miss me, if not my wife and child?" So I thought about my mum. Again I prepared for death. The same thing again, going down, down, down, convinced that any moment now the bomb upstairs would explode. And then again ― "Stop! Stop!" ― I had the same message, the same light, the feeling I'd somehow got through this, and that thoughts of my mother had rescued me. I didn't even have time to reflect on what happened a few minutes before and because of the grass I was in a euphoric state, full of happiness and life. Then the situation repeated itself. I was just beginning to enjoy myself when once more everything started to wind down. God said: "No, your mum isn't a good choice. She is not happy that you'll die, but, c'mon, let's be frank, you are 33 years old, and you've done nothing with your life. You were always such a promising child ― you'd be this or you'd be that ― but really there was nothing ever there. So actually your death will be a solution for her. It will be really horrible, of course, but she will be conscious of the fact that you could have been somebody, or, rather, that you were just about to be someone. Oh yes, and the idea of the bomb, no, no, it is not like that. You can't understand the mind of God. It is above normal understanding so all that business was just your construction. This is a typical human notion, this seeking for causes, at the end of which all will be logically explained, but no, it's not like that at all. Alex who's sleeping in the bed next to yours will suddenly get up, open his brand new knife, which he showed you earlier today, and kill you, just like that. It'll be for no reason, nothing you can explain. He'll do it out of madness." I shook Alex awake, crying, "I'm really sorry, but you're going to kill me in a minute. I forgive you." "What are you talking about?" he groaned. "Have you smoked too much dope or what?" I pleaded with him. "I don't expect you to comprehend this, but it'll happen just like that." "Okay, okay," he said, "go back to sleep." So I thought again, "Who'll miss me?" I thought about my sister. The same thing: I was going down, down, down, about to die, and I don't remember the rest because either I fell asleep or died.

'The next morning I woke up. "Shit, I'm alive!" I remember thinking God could do with me what he liked, and that my looking for a reason was the wrong attitude. It was the same with Alex in that he was wholly free to do as he liked. He could have killed me if he wanted to. There came a moment when I thought maybe I really did die. And then I thought that it was because of my sister Eva's help that I survived.'

Andrzej paused for a rare moment, allowing me time to absorb what he'd just told me. Something in me began to subside. This simply wasn't good enough, these drug-fuelled hallucinations of someone who'd gone without sleep, a measure of Slavic histrionics tossed in for good measure, and in godforsaken Rotterdam of all places. Whichever way I looked at it, this was a pothead's shaggy dog tale. Why dredge up all that Sixties moonshine, especially when its beams took almost two decades to arrive? I heard a voice in me, saying, 'This will not do, not at all. Thank you, but no thank you', and just as I was mentally packing away Andrzej's sorry case he continued.

'That would have been the end of the story except that while drinking coffee later that morning I thought again about all those earlier calculations of mine and I realised, "Oh, my God, I've made a mistake!" The date I was heading towards wasn't the 29th of September yesterday. It was the 29th of September one year earlier.'

This I could believe absolutely because the very same thing happened to me on my last birthday, when I discovered I was in fact a year younger than I thought, and, besides, there's something in me that thinks we've got it all wrong anyway. When we turn 49, for example, we are in fact entering our fiftieth year, just as when Andrzej thought he was entering his 33rd it was really his 34th year. If he was counting, as he said he was, the days from his birth, rather than from his first birthday, then his error becomes quite explicable. There is also the distinct possibility that, like me, he is close to innumerate.

'All I had been waiting for, this radical change in my life, or whatever form my death would take, took place exactly one year earlier. What was I doing then? Suddenly I remembered. One year before, on that precise date, September 29th, 1982, the boat which I'd caught in Gdansk arrived at midnight, at Folkestone, on the coast of England. It was so obviously a closure, such a precise date, and a kind of a death. And when you think I'd gone back to Poland on the same date, a couple of years before! When, later, I thought about whether I'd ever move back to Poland I thought no, probably never. What makes me think all this was written in the stars is all that nonsense of the night before, with the grass, which was so explicable. All that stuff was merely an introduction to something of real substance, a true story about a special day, and it had nothing to do with what I smoked. Also, and this is something I found in my diaries, earlier that day I had been reading the Polish Romantic poets. This bit of our history also explains my state of mind at the time. After the failure of the 1830 uprising against Russia, there was a period when they all gave up art and waited for a sign from God. There was this mystical Towianski Movement under the spell of which Adam Mickiewicz gave up writing and Juliusz Slowacki started producing mystical poetry. They were trying to make sense of what happened. They were, most of them, strongly religious. They couldn't understand why they'd lost Poland, and in their effort to ascribe meaning to this they decided it must have been a plan in God's head and so they began looking for signs. This waiting for signs can be pleasurable, especially when you are lost and trying to make sense of where you are. There is that fanciful, slightly medieval, concept that reality is a boso obvious, so boring and ok of signs. This attitude has always fascinated me, and earlier, as an art historian, I'd read much on iconography, symbols and their attributes. I had stuffed my brain with these books on symbols which, more or less consciously, allowed me to look at something and build connections and make my own stories from it. There is always in me this hope for a message. All year I had been waiting for that major event, and, here again, this is in my diaries, it occurred to me that maybe it had already happened and I had just ignored it. And this actually was the case, except that I got my dates wrong. Some time later, I was asked to write a play about this, but it was too difficult because really one needs to be telling this to someone, face to face. On the page it would seem like I was patching together a nice story. It would be so easy to shift the dates a little so as to make it work, which is what one does when one writes, but this was not literature. It was all true. We look for those gaps in logic and the key thing for me, and I am speaking out of my deepest conviction, which isn't so deep in everyday life because there we are forced to think logically most of the time, is that our knowledge of the world is nothing compared to what it will be in 200 years' time. Things will be so different that one should recognise just how pointless one's current reasoning is. Actually that area of darkness allows for fantastic hope. I do believe it is a question of focusing our attention, of noticing those strange things, and that all our accommodation of the brain works towards ignoring them simply because they disturb us. My arrival here was on St Michael's Day or Michaelmas. Michal, the Polish form of Michael, is my second name.'

I told Andrzej that I first arrived in England on September 29th, 1973, and that this also was the date of W.H. Auden's death, which I remember clearly because I was in a fish and chip shop in Dover, marvelling at the fact that fish and chips really did come wrapped in newspaper, and such was my wonderment at this simple fact of English existence that not even Auden's wrinkled face on the TV screen flickering above the counter, and the funereal tones of the newsreader, could entirely dispel my pleasure. And it was on that date, precisely twenty years later, that my first collection of poems was published, and when at the launch for the book I gave a reading from it one of the people in the audience was Auden's niece. And stranger still, for better or worse, Auden never really shone in my literary universe. I'm of another ilk altogether, closer to things that are not all close. When I told Borkowski this date also represented the closing of a chapter in my life, he cried, 'The angel's gaze!' MARIA

She is a troubling creature this one, at least to modern sensibilities, all hips and small brain, such as one finds in Venus figurines from the Palaeolithic Age. She has no purpose other than to be fertile. A pagan mother goddess, she's yet to be elevated to Theotokos ("God-bearer"), she who shall be Mary or Maria, Mother of God. For now, though, no virgin she, she's rooted in her sex. She aims to please. She's as primordial as a dinosaur egg omelette. She's got legs longer than Cyd Charisse's.

'Maybe I was being pretentious ― I was 14 or 15 at the time ― but I liked the idea of being given the name "Maria" at my confirmation. The usual male version is "Marian". I remember the bishop getting the slip of paper on which was written the name he was about to give me. "Maria?" he said. He thought for a moment. "Okay, then. Maria." Now I've begun to treat "Maria" in a more obvious colloquial way, as an extra protector in my name, just in the same way you would give anyone a name that evoked the patronage of one of the holy apostles. Holy Mary is more important and therefore gives more protection, but to begin with I wasn't especially thinking of "Maria" as the Mother of God, even though all that Catholic background is important for me. The Polish writer, Artur Maria Swinarski, was probably responsible. I remember as a child reading a book of his satiric verses and thinking how fantastic it was that a man could call himself "Maria". Rainer Maria Rilke too. You want to know certain things are allowable and so there were these two examples. When I was still at school and trying to make sense of my life, I'd get these weird ideas. I had this French auntie who lived in Warsaw, Aunt Ella ― she was really French, spoke no Polish ― and when she died I inherited from her a tricolore ribbon and a thick Petit Larousse. I remember, aged 14, looking through it at all the small reproductions of the faces of great people to see if there was anyone who looked like me, so I could live his life. It was a rather Borgesian idea, this choosing another person's life that would provide a map for mine. I didn't find anyone. Another reason I looked for another face was because when I was a teenager I was so sensitive about mine, which looked like a monkey's. As a child I sucked my thumb and, so the doctors say, developed a protruding mouth. I was called Titus, which is a nice Roman name, except that in those days it was the name of the monkey in a very popular Polish comic.'

'Do you consider yourself Catholic?'

'I say I'm Catholic and probably it's a lie because I don't practise. I haven't been to confession for thirty years. At the beginning of the 1990s, I was in Poznan and there was this small church, a kind of Romanesque structure, one of the oldest churches in the city. I noticed a priest in the darkness of the confessional, and I thought this would be a fantastic place to talk. But then I realised it would be too difficult, the obvious problem being that I would be asked to confess as sins things I do not consider sins. If there was a written list of sins then maybe I could have a discussion with him, saying, "Look, I don't think this is a sin", but then it would be awkward for the priest too because I could not promise not to do it again. I wouldn't be able to say I'd avoid those love adventures because I can't really consider them as sins. If I were really sorry for something that I thought was wrong that would be great but I can't be forced to admit to things I don't believe are crimes. Obviously with an intelligent priest maybe I could get into some kind of agreement that, yes, I am alone with my soul. But there is also something beautiful in the idea of confession, the humility of meeting another person who might be stupider than you. There again, like most Poles I am emotionally attached. I cherish the Catholic rootedness in pagan times, especially with the images and all those emotional elements which in Protestantism I find too much reduced to mere letters and words. With the cult of saints, and all the physicality, that part of the Mother Church is so much more sensual, whereas for Protestants I think it is very much the religion of the Book. I think that the bridge between pagan cults and cults of saints and the usage of images and sculptures is more deeply rooted in the past, and that the cleansing which came with the Renaissance and the Reformation made the Church all that much more controlling. I might have enormous respect for theological knowledge, but for me the vagueness and physicality are more attractive. At the same time it is the very thing that irritates me when I go to a Polish church. There is all that theatricality, so much of it and not enough thinking, but those two elements do provide some strange emotional power. The relics, for example, are fantastic.'

'Would it be a mistake,' I asked him, 'to attribute your paintings and prints to "Andrzej" and the glass paintings to "Maria"? There is, in the latter, the iconography one associates with religiously inspired art.'

Borkowski seemed to leap at this. Yes, yes, yes.

'I really enjoyed making those glass paintings partly because I was really missing, and I still do, that fantastical world of iconography and legend. I did a few in Poland, mostly as presents for people. Those were not directly connected with religious subjects, whereas the ones I did here are rather more so. The situation from which the glass paintings arose was that I'd booked a space in the POSK [Polski Osrodek Spoleczno-Kulturalny] Gallery in Hammersmith, and I thought rather than show my prints wouldn't it be nice to have something that would directly address a mainly Polish audience. I really wanted to connect those paintings with literature, with scrolled texts hidden behind them. One of the big childhood inspirations for me was Kipling's Just So Stories. I loved the richness of that connection between word and image. I thought that maybe I, too, could try to manipulate the tradition, make adaptations to it, and find other stories behind those images, which is something contemporary art doesn't allow much space for. I was inspired by Islamic art, Mogul miniatures in particular. I concentrate mainly on contemporary art, and so I really miss those lectures on mediaeval iconography and also those stories about the saints, the fantastic imagination you find in them. It's a pity it is so difficult to communicate this because already it has become lost knowledge. Also I really like those strong, vibrant Mexican colours, the way they clash, which is so joyful, so physical.'

And then there is Andrzej's other art that is much darker in tone, and which he attributes to a single letter.

'N.'

This one's from a child's literature, some fable whose telling is said to make the poor mite sleep easy. Sweet dreams, then. It's no accident this creature has six fingers. What Borkowski needed to do was to find a rock that would split his image. What he had by way of inspiration was already shelved in his vast mental store. At one point in his career, inspired by a painted image on the wall of a caveman's cave, he adopted a six-fingered hand as his logo. It is what made him, what makes any artist, an alien. Small wonder he finds beautiful the name that in others, especially those coming to this country for the first time, inspires a sense of grievance: Alien Registration Office (ARO). There, quite happy to be an alien, he applied for his resident's certificate. Did they ask for his fingerprints, all six of them? The most famous polydactyl was Goliath: 'And yet again there was war at Gath, where was a man of great stature, whose figures and toes were four and twenty, six on each hand, and six on each foot and he also was the son of the giant.' (1 Chronicles 20:6)

Hannibal Lector had six fingers until he decided to remove one.

Borkowski appeared to have only five.

'I did a peculiar drawing of four monsters in a cave, in front of a gate. Only later did I think about it more. What did it mean? I then got the idea that those four beings were all me inside in my mother's womb and that they would join together as one, as a single person, before going through that gate into the world outside.'

'Andrzej is a man's name and Michal, that birdlike creature, is an angel's, and there, on the left of the picture, is Maria although she's pretty horrible. It was obvious to me there was something missing. Who was that fourth figure? So I kept thinking about the drawing and all that business about wholeness, those four elements in me which are like cardinal points ― man, woman, angel … and then I realised I needed another identity, one that had to do with sex, earth, darkness, the body, maybe an animal of some kind, or even a devil which in me would be the angel's opposite. I settled on the letter "N". Actually it came to me naturally. I didn't want it to be a full name because "N" is the Nameless One ― Jules Verne's Captain Nemo, which in Latin means 'no man' or "no-body", or Odysseus when he is asked his name by Polyphemus and he replies "Nobody". I have a passion for that letter. It's usually connected with water and fish and with the deeps. There is a beautiful chapter in a book [Fundamental Symbols: The Universal Language of Sacred Science] by the French writer, René Guénon, who was a convert to Islam. 'N' is noon in both Hebrew and Arabic. The Arabic with its open shape and dot above supposedly represents a seed in a cauldron, and also, according to Guénon, it suggests Jonah in the whale, in that darkness before he returns as the human being he was before. Guénon, probably, is what most influenced my choice. And then there's all that cabbalistic speculation in which "N" equals 50 but it's too complicated to go into here. "N" is for me such a fantastic subject. You enjoy the possibilities! I like the idea of the Portuguese writer, Fernando Pessoa, creating several identities for himself and persisting with them. When I took on "N" I thought it would be a good idea to define more those genders and characters that are part of me. I could associate with this one or that one, and then more fully develop it. "N" is also an anarchic figure, although I wonder how much I allow him to be. I made some pornographic, on the edge of nearly disgusting, drawings that could be easily attributed to him.'

'Your experience in Rotterdam belongs to which side.'

'I don't know! Who was talking? I really don't know. I think maybe all four were endangered there. My hope was to die in order to be reconstructed in some higher form, but I didn't go any further. I'm still immature.'

Immaturity is an obsession in modern Polish literature, especially in the work of Witold Gombrowicz, it being something one either rejects or embraces. Would this have been the case had it not been for the fact that all too often in Poland's history adulthood was rudely imposed upon childhood? Were its most beautiful martyrs not always children?

All Four into One Go

A crash in the Alps, a real one, marked the beginning of the end for Hesitate and Demonstrate. Another crash, a spurious one, was engineered by people without faces. An EEC dictate stipulated that the company would now have to seek European money rather than funds from individual countries. With this came other kinds of restrictions ― having to employ local actors, for example ― which would go against the artistic vision of a company that allowed for hardly any division between its creators and actors. Blandness is all. In 1985, the company went bankrupt and for Borkowski, apart from a brief spell elsewhere, this marked the end of his career in theatre. It was, of course, a certain kind of theatre. It would need to be in order to accommodate him. In 1986, he returned to London and went to the Courtauld Institute where he got a second MA in art history, which gradually led to a post at Brighton University where he still teaches.

I couldn't help but notice a faltering, an actual slowing down, in Borkowski's voice.

'Obviously I'm nowhere. The fact that I came to London so late in life probably did not allow me to ever be completely here. I was dragging behind me those thirty-three years and all those attitudes that had been much earlier created in me. On the other hand, I feel a sense of great freedom here, and I can see all the possibilities ― I see them, and yet I am not able to use them as much as I'd like to because I'm still haunted by the ghosts of the past. I really cut it when I first came here. I was doing another kind of theatre, and was successful at it. Obviously there were ups and downs such as any young person might have, but the moment I entered this empty space, after the theatre collapsed, I was on my own. It was now up to me to find something else, and among the various options that presented themselves was finding this reconnection to Poland. I wrote some small articles for the Polish Daily (Dziennik Polski). At first I treated this as a small, quite unimportant, patriotic gesture, but this, I soon discovered, was an umbilical cord that had never been cut. And so I continued to write short articles, mostly reviews of exhibitions. You feel there's an opening for a while and you think, yes, you've had a good response, and you have found a place for yourself. You didn't fight for it, they invited you, but now it's become that big mother. You can be the most important Polish critic there, rather than try to be an important British one. You find those niches and suddenly you are sucked into what feels very much like a trap.'

'And so, what is the nature of this other place, this London within a London?'

'Very early on, whenever I met up with Poles, I felt there was a normal British society, and then there was this copy of it which is Polish immigrant society recreated somewhere on the outskirts of the former. It bears no relation to the bigger one, but because it's small it's so much easier to manipulate. Meanwhile, you still see that other world in front of you, which is out there on the street. I keep returning to this painful metaphor of a Poland in miniature, as being a dangerous place to step into, because once you're inside you are seduced by it. You might have the same capabilities on the outside, but they're no longer as important because it's too big, this London where you are just one person standing next to millions. I'm terrified by how completely isolated I have become. Such articles as I write are mainly for the Polish press and even my exhibitions are for a mainly Polish audience. I do not have any part now in normal British cultural life. I never learned how to. That's really a problem of the will, however, and of not knowing what I want. I'm too much of a surfer. I enjoy the fact I'm on a wave. I never looked for work. Did I apply for that job in Brighton? No. One day somebody asked me to give a lecture. Yes, why not.Will you give another one? Yes, why not. It wasn't like I was choosing something. I was talking to my student about that Nietzschean will to power, which I probably despise, but then I think it's something missing in me. I have allowed myself to be swallowed by those huge cosmoses. I don't really get to make my point. My question to Grotowski was this: "Is it ethical to say, I'm here." I want to be in total empathy with everything, but basically it's a kind of mirror in which I am not reflected at all because I'm everything and everybody. I think, "Why should they listen to me? I should be listening to you." I'm speaking out of the attitude that one shouldn't impose oneself. The things I do are the things that simply happen to me, that are dragged out of me, which are born of circumstance rather than of having to make decisions. People say, "Oh, would you like to do this?" and so I do it because it's another interesting adventure. You go with it because you are greedy and because you want to squeeze life to the maximum, but squeezing is not just accepting ― it is also deciding whether to take it or not. There is a frightening richness of possibilities.

'There was this famous figure in Poland, at the beginning of the last century, Franciszek Fiszer, a huge man with a beard and renowned for his gourmandise and his wit and humour. He would come like the seasons to Warsaw, to the Ziemianska Café in spring, spend all day eating and drinking with writers and artists, and then, in late autumn, he would disappear into the residence of a wealthy cousin where during the winter months he'd do nothing but read. The thing about him is he didn't leave anything of his own behind, but he was in everyone's diaries. Fiszer lived, his material was life, and I remember how for me he represented another option in life. Is it about solidifying, producing something for eternity, or is it about squeezing that life as much as possible? I'm pretty sure I didn't really squeeze it all but at least I have been greedy. I don't care so much about leaving something behind.

'What is London to me? Well, there is that Polish London, which is quite a strong presence. I never wanted to belong to it but I did in the end. I'm teaching in Brighton, and maybe I was tempted to move there, thinking it would be easier to handle, but I didn't do so because of that richness I recognise. I'm conscious of not having tasted enough of London. There are still Indian and Jewish areas to explore. I'm angry sometimes about being too much inside Polish London because I'd like to learn more about the other ones. It's also a London of the mind because I lived in different parts of it and had different experiences and so when I go through it now I find myself travelling in time. I go to a certain area and I remember this is where I had my asthma attack, I go somewhere else, Notting Hill, and this is where I was paid with hash for my drawings, and then I go to Camden Town, which was the base for Hesitate and Demonstrate, and then Charing Cross Road with all those amazing book shops. It is travelling through your life. So obviously, in that respect, it is my London. I remember trying out this experiment with regard to its geometry, which is something I did in Poland once.

When I fell in love with Gabriela I was living in Warsaw and she was living in Gdansk and I remember taking a compass and making these circles, and then I discovered that the points where I was, where I first met her, and where we spent our first holiday together, made a perfect triangle. I tried to do something similar with London, an art project involving a map of the city, finding all the places I lived in, marking them on transparent paper and then, choosing a centre, superimposing this on a map, trying to see if by doing so I could derive any possible poetic meanings from this. Once again, I was looking for signs. I had a problem, though, because I didn't know where London's centre was. Was it the City? Was it Piccadilly Circus? Was it Nelson's Column in Trafalgar Square?'

I will stop here. It is not where we stopped in our conversation, but it's as good a place to stop as any because, as Ezra Pound writes, 'What is the use of talking, and there is no end of talking,/There is no end of things in the heart.' (Actually it's from the Chinese of Rihaku, but it's Ezra all the same.) The sense one has of Borkowski is that with him one could go on forever, for such are the twists and turns of his remarkable mind. And then, of course, one trembles a little at the idea of forever because eternity comes at the expense of shape. Maybe, though, this is not really such a good place to leave Borkowski because when I last saw him he was in a black hole. I could see it in his face. I could hear it in his voice. It is no place to leave him, not when he dazzles the eye with his luminous images, and just when he seems to be on the verge of some fresh adventure. And so I shall settle where I began, on an image that is more a product of his thinking than I could have at first imagined, and which contains the signs he so fondly looks for in every place.